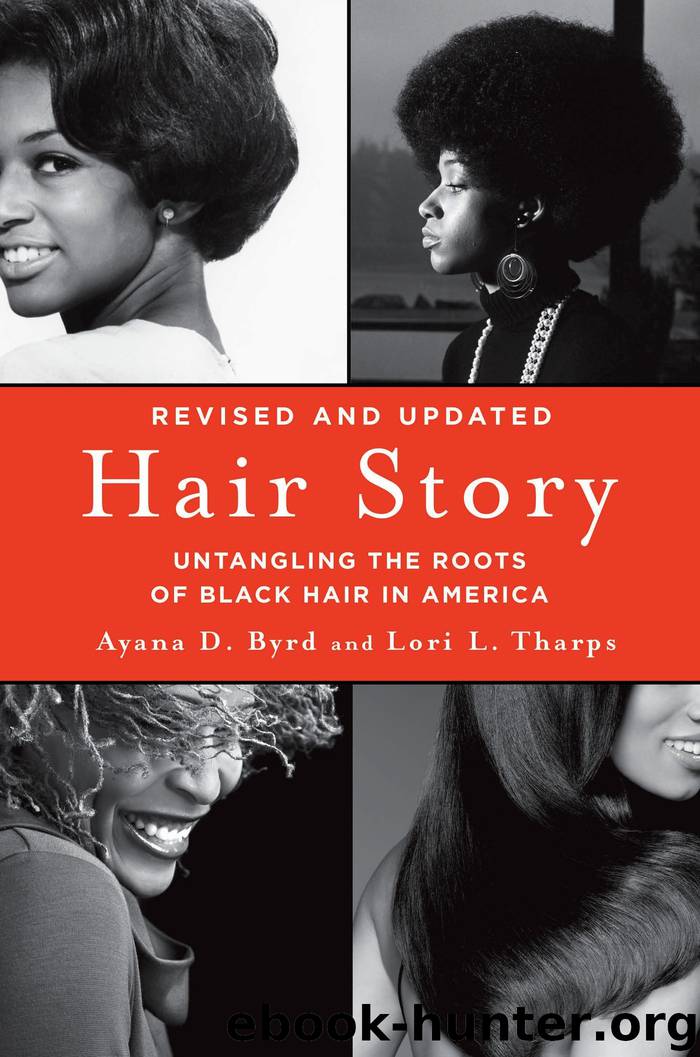

Hair Story by Ayana Byrd & Lori L. Tharps

Author:Ayana Byrd & Lori L. Tharps [Byrd, Ayana & Tharps, Lori L.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: St. Martin's Press

Published: 2014-04-05T21:00:00+00:00

Locs get trendy in America, 1991. From the authors’ collection.

The assertion that African-Americans with dreds were wearing the style only as a fashion oversimplifies the situation. First, even as a fashion statement the embracing of dredlocs was significant in that it was a negation of all things Black hair was “supposed” to look like, namely straight and neat. Second, many were wearing the look as a way to connect visibly to their African roots by celebrating the Blackness of their hair, hair that was able to grow into such a style. Last, Rastafarian assertions that Black Americans were co-opting “their” style are based on questionable logic. Rastafarians did not “invent” dredlocs; they adopted the look from Kenyan soldiers, but the style dates to before the fifth century, when Bahatowie priests of the Ethiopian Coptic Church locked their hair. The sadhus, a nomadic group of Hindu holy men, have worn their hair in this way since the pre-Christian centuries as a symbol of a covenant between themselves and Shiva, the god of destruction and regeneration. From Japan’s Rasta-Buddhists to Maori warriors in New Zealand, various groups have adopted dredlocs as a style endowed with symbolism, reverence, and aesthetic meaning. It is a hairstyle over which no group can claim ownership.

Yet and still, dredlocs and their commodification in Black American culture made an interesting statement about the evolution of Black hair. Was it possible for Blacks to appropriate something that was Black in its essence? While debates and opinions raged on, the style was spreading to other groups outside the African-American community. By the early nineties, particularly in California, Whites and Asians had begun to wear the style. A Venice Beach hair salon, Papers Scissors Rock, managed by Japanese-American Masao Miyashiro, charged two hundred dollars to begin dreds for people in 1994. Only 15 percent of their clientele was African-American. Some were Asian, particularly Japanese tourists, but most were white bicycle messengers, surfers, and other young white Californians. Papers Scissors Rock was relatively inexpensive compared with some other salons that specialized in dreding hair and charged up to a thousand dollars. The cost was so high because of the time and effort that went into getting non-nappy hair to loc. It presents a more daunting problem than napping up unkinky hair to make an Afro. Some solutions for locing unwilling hair include washing it with beeswax or baking soda, coating the hair with a chemical relaxer to break down the structure of the hair, using Krazy Glue to form the knots around which the dreds are coiled, and putting toothpicks into the newly formed locs to encourage them to grow downward. Some people simply had extensions of dreded hair added to their own.

As with Bo Derek’s wearing of cornrows, some Black people were not pleased with non-Blacks wearing dredlocs. “I try not to care and to think to each his own,” says twenty-something Brooklyn writer and former dred wearer Karen Good. “But somewhere deep inside of me, it just doesn’t sit well.”

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

China Rich Girlfriend by Kwan Kevin(4557)

The Curated Closet by Anuschka Rees(2964)

How to Make Your Own Soap by Sally Hornsey(2891)

The Wardrobe Wakeup by Lois Joy Johnson(2776)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2654)

Bossypants by Tina Fey(2522)

Life of Elizabeth I by Alison Weir(2071)

The Little Book of Lykke by Meik Wiking(2038)

Beard by Rainwaters Matthew(2000)

The Finnish Way by Katja Pantzar(1987)

How to Be a Bad Bitch by Amber Rose(1960)

Worn in New York by Emily Spivack(1960)

The Apron Book by EllynAnne Geisel(1946)

GQ How to Win at Life by Charlie Burton(1842)

Beauty Sick by Renee Engeln PhD(1841)

Perfume by Jean-Claude Ellena(1815)

GQ How to Win at Life: The expert guide to excelling at everything you do by Burton Charlie(1755)

Lagom by Niki Brantmark(1716)

Younger Skin Starts in the Gut by Nigma Talib(1686)